Health problems that are common and known in the Cane Corso breed

- Canine Hip Dysplasia (HD), often called Degenerative Joint Disease (DJD), or Osteoarthritis Hip dysplasia is a multifactorial abnormal development of the coxofemoral joint in large dogs that is characterized by joint laxity and subsequent degenerative joint disease. Excessive growth, exercise, nutrition, and hereditary factors affect the occurrence of hip dysplasia. The pathophysiologic basis for hip dysplasia is a disparity between hip joint muscle mass and rapid bone development. As a result, coxofemoral joint laxity or instability develops and subsequently leads to degenerative joint changes, eg, acetabular bone sclerosis, osteophytosis, thickened femoral neck, joint capsule fibrosis, and subluxation or luxation of the femoral head. Clinical signs are variable and do not always correlate with radiographic abnormalities. Lameness may be mild, moderate, or severe, and is pronounced after exercise. A “bunny-hopping” gait is sometimes evident. Joint laxity (Ortolani sign), reduced range of motion, and crepitation and pain during full extension and flexion may be present. Radiography is useful in delineating the degree of arthritis and planning of medical and surgical treatments. Standard ventrodorsal views of sedated or anesthetized animals can be graded by the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals, or stress radiographs performed and joint laxity measured (Penn Hip). Treatments are both medical and surgical. Mild cases or nonsurgical candidates (due to health or owner constraints) may benefit from weight reduction, restriction of exercise on hard surfaces, controlled physical therapy to strengthen and maintain muscle tone, anti-inflammatory drugs (eg, aspirin, corticosteroids, NSAID), and possibly joint fluid modifiers. Surgical treatments are also available. -Merik Veterinary Manual

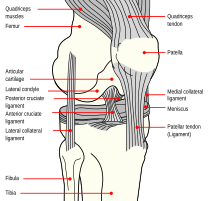

Illustration of the ligaments of the knee, including the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments

Illustration of the ligaments of the knee, including the anterior and posterior cruciate ligamentsCruciate ligaments (also cruciform ligaments) are pairs of ligaments arranged like a letter X.They occur in several joints of the body, such as the knee. In a fashion similar to the cords in a toy Jacob's ladder, the crossed ligaments stabilize the joint while allowing a very large range of motion. Cruciate ligaments occur in the knee of humans and other bipedal animals and the corresponding stifle of quadrupedal animals, and in the neck, fingers, and foot.

- The cruciate ligaments of the knee are the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). These ligaments are two strong, rounded bands that extend from the head of the tibia to the intercondyloid notch of the femur. The ACL is lateral and the PCL is medial. They cross each other like the limbs of an X. They are named for their insertion into the tibia: the ACL attaches to the anterior aspect of the intercondylar area, the PCL to the posterior aspect. The ACL and PCL remain distinct throughout and each has its own partial synovial sheath. Relative to the femur, the ACL keeps the tibia from slipping forward and the PCL keeps the tibia from slipping backward.

- Another structure of this type in human anatomy is the cruciate ligament of the dens of the atlas vertebra, also called "cruciform ligament of the atlas", a ligament in the neck forming part of the atlanto-axial joint.

- In the fingers, the deep and superficial flexor tendons pass through a fibro-osseous tunnel system – the flexor mechanism – of annular and cruciate ligaments called pulleys. The cruciate pulleys tether the long flexor tendons. The number and extent of these cruciate and annular ligaments varies among individuals, but three cruciate and four or five annular ligaments are normally found in each finger (usually referred to as, for example, "A1 pulley" and "C1 pulley"). The thumb has a similar system for its long flexor tendon but with a single oblique pulley replacing the cruciate pulleys found in the fingers.

- The human foot has a cruciate crural ligament, also known as inferior extensor retinaculum of foot. The equine foot has a pair of cruciate distal sesamoidean ligaments in the metacarpophalangeal joint. These ligaments can be seen using computed tomography.

Rupture

Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament is one of the "most frequent acquired diseases of the stifle joint"in humans, dogs, and cats; direct trauma to the joint is relatively uncommon and age appears to be a major factor.

Cruciate ligament injuries are common in animals, and in 2005 a study estimated that $1.32 billion was spent in the United States in treating the cranial cruciate ligament of dogs.

Rupture in canines and surgical repair techniques

- In animals the two cruciate ligaments that cross the inside of the knee joint are referred to as the cranial cruciate (equivalent to anterior in humans) and the caudal cruciate (equivalent to the posterior in humans). The cranial cruciate ligament prevents the tibia from slipping forward out from under the femur.

- Stifle injuries are one of the most common causes of lameness in rear limbs in dogs, and cruciate ligament injuries are the most common lesion in the stifle joint. A rupture of the cruciate ligament usually involves a rear leg to suddenly become so sore that the dog can barely bear weight on it.

- How a rupture can occur:

- There are several ways a dog can tear or rupture the cruciate ligament. Young athletic dogs can be seen with this rupture if they take a bad step while playing too rough and injure their knee. Older dogs, especially if overweight, can have weakened ligaments that can be stretched or torn by simply stepping down off the bed or jumping.

- Large overweight dogs are at more risk for ruptures of the cruciate ligament. In these instances it is common to see a rupture in the other leg within a year’s time of the first rupture.

- Common breeds that are seen with cruciate ligament ruptures:

- In recent survey’s some of the large breed dogs that seem to be at risk for obtaining these ruptures were: Neapolitan mastiff, Newfoundland, St. Bernard, Rottweiler, Chesapeake Bay retriever, Akita, and American Staffordshire terrier.[ However, other breeds have been observed with these ruptures, such as: Labradors, Labrador crossbreeds, Poodles, Poodle crossbreeds, Bichon Frises, German Shepherds, Shepherd crossbreeds, and Golden Retrievers.

- Diagnosis:

- History, palpation, observation and proper radiography is important in properly assessing the patient. The key in diagnosing a rupture of the cruciate ligament is the demonstration of an abnormal gait in the dog. Abnormal knee motion is typically observed and diagnosis of a rupture can be made by performing the drawer sign test.

- The Drawer Sign:

- The examiner stands behind the dog and places a thumb on the caudal aspect of the femoral condylar region with the index finger on the patella. The other thumb is placed on the head of the fibula with the index finger on the tibial crest. The ability to move the tibia forward (cranially) with respect to a fixed femur is a positive cranial drawer sign indicative of a rupture (it will look like a drawer being opened).

- Another method used to diagnose a rupture is the tibial compression test, in which a veterinarian will stabilize the femur with one hand and flex the ankle with the other hand. The tibia will move abnormally forward if a rupture is present.

- For proper diagnosis sedation is typically needed since most animals tend to be tense or frightened at the vet’s office. If the animal tenses its muscles, temporary stabilization of the knee can be observed which would prevent demonstration of the drawer sign or tibial compression test.

Radiographs are typically necessary to identify whether bone chips, from where the ligament attaches to the tibia, are present. This can occur when the cruciate ligament tears, and if found will require surgical repair.

- Surgical Repair

- Three surgical techniques are commonly used

- Extracapsular Repair

- Any bone spurs are removed and a large suture is passed around the fabella behind the knee through a drilled hole in the front of the tibia. This surgical procedure tightens the joint to prevent the drawer motion, and the suture that is put in place takes the job of the cruciate ligament for approximately 2 to 12 months after surgery. The suture will eventually break and the dog will have its own healed tissue that will hold the knee in place.

- Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy

- This surgery uses biomechanics of the knee joint and is meant to address the lack of success seen in the extracapsular repair surgery in larger dogs. A stainless steel bone plate is used to hold the two pieces of bone in place. This surgery is complex and typically costs more than the extracapsular repair.

- Tibial Tuberosity Advancement

- This surgery aims at advancing the tibial tuberosity forward in order to modify the pull of the quadriceps muscle group, which in turn helps reduce tibial thrust and ultimately stabilizes the knee. The tibial tuberosity is separated and anchored to its new position by a titanium or steel cage, “fork”, and plate. Bone graft is used to stimulate bone healing.

- Canine Panrosteitis (Growing Pains, Pano) Panosteitis is a spontaneous, self-limiting disease of young, rapidly growing, large and giant dogs that primarily affects the diaphyses and metaphyses of long bone. The exact etiology is unknown, although stress, infection, and metabolic or autoimmune causes have been suspected. The pathophysiology of the disease is characterized by intramedullary fat necrosis, excessive osteoid production, and vascular congestion. Endosteal and periosteal bone reactions occur. Clinical signs are acute, cyclical, and involve single or multiple bone(s) in dogs 6–16 months old. Animals are lame, febrile, inappetent, and have palpable long bone pain. Radiography reveals increased multifocal, intramedullary densities and irregular endosteal surfaces along long bones. Therapy is aimed at relieving pain and discomfort; oral NSAID, opioids, or corticosteroids can be used during periods of illness. Excessive dietary supplementation in young, growing dogs should be avoided. -Merik Veterinary Manual

- Canine Bloat (Gastric Torsion, Gastric Dilation-Volvulus, or GDV) Gastric dilatation and volvulus (GDV), commonly called “bloat” or “torsion,” is an extremely serious medical condition where a dog’s stomach becomes filled with gas that cannot escape. The stomach also can rotate around its short axis, often carrying the spleen along for the dangerous ride. By itself, “bloat” technically refers only to the gaseous distension of the stomach, without the flipping-over, or “torsion,” part of the condition. Think of it as if the stomach is a balloon that keeps filling with gas, but the “escape route” is twisted or tied off. Eventually, the balloon will rupture. Similarly, the stomachs of dogs suffering from gastric dilatation and volvulus can rupture, spilling intestinal contents into the abdominal cavity. Bloat is life-threatening and requires immediate and aggressive medical attention if the dog is to survive. Without emergency treatment, bloat can be fatal within a matter of hours of the appearance of clinical signs. The precise triggers of GDV are not well-understood. Why this process happens is still a medical mystery. A number of different contributing factors have been suggested, but none have been proven. Dogs that eat a single, large meal of dry kibble and then drink large amounts of water and/or become active seem predisposed to bloat. Bloat is a life-threatening condition. Without immediate medical care, the chance of survival is extremely low. If you own a large deep-chested dog – or indeed any dog -- please make sure that you have a good relationship with your local veterinarian and that you are familiar with the signs of this condition, so that if it happens to one of your dogs, you are prepared to deal with it immediately. -Petwave

- Canine Conformational Abnormalities affecting the Eye:Entropion Entropion is the turning in of the edges of the eyelid (usually the lower eyelid) so that the lashes rub against the eye surface. An inversion of all or part of the lid margins that may involve one or both eyelids and the canthi. It is the most frequent inherited eyelid defect in many canine and ovine breeds, and may also follow cicatrix formation and severe blepharospasm due to ocular or periocular pain. Inversion of the cilia (or eyelashes) or facial hairs causes further discomfort, conjunctival and corneal irritation, and if protracted, corneal scarring, pigmentation, and possibly ulceration. Early spastic entropion may be reversed if the inciting cause is quickly removed, or if pain is alleviated by everting the lid hairs away from the eye with mattress sutures in the lid, by subcutaneous injections (eg, of procaine penicillin) into the lid adjacent to the entropion, or by palpebral nerve blocks. Established entropion usually requires surgical correction. -Merik Veterinary Manual

- Canine Ectropion Ectropion is the turning out of the eyelid (usually the lower eyelid) so that the inner surface is exposed. A slack, everted lid margin, usually with a large palpebral fissure and elongated eyelids. It is a common bilateral conformational abnormality in a number of dog breeds. Contracting scars in the lid or facial nerve paralysis may produce unilateral ectropion in any species. Conjunctival exposure to environmental irritants and secondary bacterial infection can result in chronic or recurrent conjunctivitis. Topical antibiotic-corticosteroid preparations may temporarily control intermittent infections, but surgical lid-shortening procedures are often indicated. Mild cases can be controlled by repeated, periodic lavage with mild decongestant solutions. -Merik Veterinary Manual

- Canine Cherry-Eye (Canine Nictitans Gland Prolapse) Cherry eye is the common term used to refer to canine nictitans gland prolapse, a common eye defect in various dog breeds where the gland of the third eyelid known as the nictitating membrane prolapses and becomes visible. Commonly affected breeds include large breed dogs or breeds with loose skin on the face or droopy skin around the eyes. Cherry eye may be caused by a weakness in the connective tissue surrounding the gland. It appears as a red mass in the inner corner of the eye, and is sometimes mistaken for a tumor. After gland prolapse, the eye becomes chronically inflamed and there is often a discharge. Treatment can include tacking the gland back in place, or removal of the prolapsed gland. -Wikipedia

- Canine Demodicosis (Demodectic Mange, Demo, Demodex, Demodex Mange, or Red Mange) Demodectic Mange is caused by a sensitivity to and overpopulation of Demodex canis as the animal's immune system is unable to keep the mites under control. Demodex is a genus of mite in the family Demodicidae. Demodex canis occurs naturally in the hair follicles of most dogs in low numbers around the face and other areas of the body. In most dogs, these mites never cause problems. However, in certain situations, such as an underdeveloped or impaired immune system, intense stress, or malnutrition, the mites can reproduce rapidly, causing symptoms in sensitive dogs that range from mild irritation and hair loss on a small patch of skin to severe and widespread inflammation, secondary infection, and—in rare cases—a life-threatening condition. Small patches of demodicosis often correct themselves over time as the dog's immune system matures, although treatment is usually recommended. -Wikipedia

- Canine Epilepsy The 1st diagnosis of Epilepsy has been proven early 2015 in Australia, definitely concerning for breeders in Australia and advise people to ask as many questions regarding this.Canine epilepsy is characterized by recurrent, unprovoked seizures. Canine epilepsy is often genetic. There are three types of epilepsy in dogs: reactive, secondary, and primary. Reactive epileptic seizures are caused by metabolic issues, such as low blood sugar or kidney or liver failure. Epilepsy caused by problems such as a brain tumor, stroke or other trauma is known as secondary or symptomatic epilepsy. In primary or idiopathic epilepsy, there is no known cause. This type of epilepsy is diagnosed by eliminating other possible causes for the seizures. Dogs with idiopathic epilepsy experience their first seizure between the ages of one and three. However, the age of diagnosis is only one factor in diagnosing canine epilepsy. One study found a cause for the seizures in one-third of dogs between the ages of one and three, indicating secondary or reactive rather than primary epilepsy. -Wikipedia

- Canine Preeclampsia This is also a new diagnosis however it is known to a few kennels, there is a lot of research still to be done on this topic in Australia but we have some info regarding it. Canine preeclampsia is a life-threatening condition during pregnancy and after delivery when there is a deficiency of calcium in the blood stream. The medical condition for low blood calcium is called hypocalcemia. This condition also can occur after the female dog has delivered her pups and when she nurses them she loses too much calcium. There are two forms of this disorder which are called preeclampsia and eclampsia. Eclampsia is a more severe form of preeclampsia. Both of these disorders are more commonly known as milk fever. The symptoms of preeclampsia in dogs are tetany; this is a life threatening condition. If the condition goes on to the more serious form, eclampsia, the dog may also have seizures. The dog could die very quickly. A dog with eclampsia or preeclampsia will have symptoms that include trembling all over; this is what is referred to as tetany. The dog may not be able to walk because she will be extremely week from an electrolyte disturbance. The dog will appear very sick and have a worried expression on her face. She can’t talk to you, but you will definitely know that something is wrong by her body posture and the look on her face that seems to say “please help me.” In full blown eclampsia the dog can have seizures and go into a coma and die.

- This surgery aims at advancing the tibial tuberosity forward in order to modify the pull of the quadriceps muscle group, which in turn helps reduce tibial thrust and ultimately stabilizes the knee. The tibial tuberosity is separated and anchored to its new position by a titanium or steel cage, “fork”, and plate. Bone graft is used to stimulate bone healing.

- Three surgical techniques are commonly used